Narcan is a cornerstone in the treatment of opioid overdose. It reverses life-threatening respiratory depression, restores consciousness, and often brings dramatic results. But in some cases, this abrupt reversal can lead to acute pulmonary edema, even in young and otherwise healthy patients [1].

This article explores why this occurs, how to recognize it, and what to do when it happens.

The Physiology of Opioid Overdose

When a person overdoses on opioids, their central nervous system is suppressed. Respiratory rate slows—or stops entirely. Hypoventilation leads to hypercapnia and hypoxia. Muscle tone collapses, and the airway becomes partially or fully obstructed [2].

At this point, the patient may appear flaccid, cyanotic, or apneic. Their ability to draw in air is severely compromised, often resulting in inadequate negative pressure to move air through the airway.

The Narcan Effect: Sudden Reversal of Respiratory Arrest

When Narcan is administered, especially as a bolus IV push, the effects are rapid and dramatic. The patient may transition from an unresponsive state to sudden alertness or agitation. More critically, they often attempt to breathe forcefully—before airway tone has returned or obstruction has cleared [3].

This scenario creates a setup for negative pressure pulmonary edema (NPPE).

Negative Intrathoracic Pressure: The Hidden Hazard

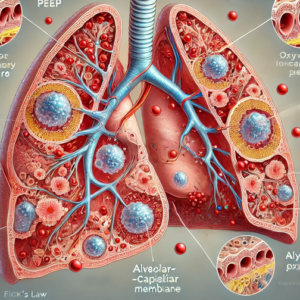

When a patient attempts to inhale against a partially obstructed airway, they generate massive negative intrathoracic pressure. This is akin to creating a vacuum in the chest.

Here’s what happens physiologically:

-

The diaphragm contracts downward.

-

Air cannot enter effectively due to soft tissue collapse, vomit, or residual opioid-induced muscle flaccidity.

-

This creates intrapulmonary and intra-alveolar pressures far below atmospheric pressure, drawing blood rapidly into the pulmonary vasculature.

-

Venous return increases, but left ventricular output may be impaired, causing a backup in the pulmonary capillaries [4][5].

-

The capillary hydrostatic pressure increases, while alveolar pressure drops—creating a gradient that pushes plasma and fluid into the alveoli, resulting in pulmonary edema [4][6].

This is not a fluid overload or a cardiac failure scenario. It’s a mechanical-pressure imbalance that mimics non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Recognizing Pulmonary Edema After Narcan

Clinical signs often appear within minutes of Narcan administration:

-

Crackles/rales upon auscultation

-

Pink, frothy sputum

-

Hypoxia that doesn’t resolve with supplemental oxygen alone

-

Tachypnea, dyspnea, and signs of increased work of breathing

-

In some cases, confusion or agitation related to hypoxia, not withdrawal [6][7]

This can happen even with correct Narcan dosing and no provider error. Recognition is critical.

Management Strategy

1. Support Oxygenation and Ventilation

-

Apply high-flow oxygen immediately.

-

Use CPAP if the patient is conscious and cooperative.

-

If the patient deteriorates or cannot maintain their airway, proceed to intubation with lung-protective strategies.

-

Use PEEP to help push fluid out of the alveoli and re-expand collapsed lung units [8].

2. Avoid Over-Bagging

-

Do not aggressively bag the patient.

-

Use controlled, low-tidal-volume ventilation to avoid worsening the pressure gradient [9].

3. Titrate Narcan, Don’t Bolus

-

Use just enough Narcan to restore respiratory effort, not full consciousness.

-

Full-dose reversal in opioid-dependent individuals often causes agitation, hypertension, and increased respiratory effort, worsening NPPE risk [3][10].

4. Pharmacological Management: Nitrates

In selected patients—particularly those hypertensive or with signs of elevated preload—nitrates (e.g., IV or sublingual nitroglycerin) may help:

-

Reduce preload, thereby lowering pulmonary capillary pressure

-

Improve alveolar-capillary gradient, reducing further fluid shift

-

Help unload the heart if underlying cardiac strain is contributing

Use nitrates only if blood pressure is sufficient, and in a controlled environment [11].

5. Cautious Diuretic Use

-

Diuretics such as furosemide may be helpful in hospital settings, but are not first-line in the prehospital setting, especially if the patient is hypovolemic from overdose or emesis [6].

Takeaway Message

Pulmonary edema after Narcan isn’t rare because Narcan is dangerous. It’s rare because most providers aren’t looking for it.

This is a complication of physiology—not pharmacology. Understanding the interplay between airway obstruction, catecholamine surge, intrathoracic pressure changes, and fluid dynamics allows us to anticipate and manage it effectively.

If you see hypoxia, crackles, or worsening respiratory distress after Narcan—don’t dismiss it as anxiety or withdrawal. It might be a lung full of fluid, not a bad attitude.

Be the provider who doesn’t just reverse the overdose—but manages what comes next.

References

-

Sporer KA. Acute heroin overdose. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(7):584-590.

-

Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):146-155.

-

Wermeling DP. A response to the opioid overdose epidemic: naloxone nasal spray. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2013;3(1):63-74.

-

Fremont RD, Kallet RH, Matthay MA, Ware LB. Acute lung injury after opioid overdose. Chest. 2007;132(2):646-649.

-

Bhattacharya M, Kallet RH, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Negative-pressure pulmonary edema. Chest. 2016;150(4):927-933.

-

Lang SA, Duncan PG, Shephard DA, Ha HC. Pulmonary oedema associated with airway obstruction. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37(2):210-218.

-

Pang PS, Komisaruk E, et al. Pulmonary complications of heroin overdose. Chest. 1981;80(5):563–566.

-

Tobin MJ. Principles and Practice of Mechanical Ventilation. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2013.

-

Davis DP, Peay J, Sise MJ, Vilke GM. Prehospital airway and ventilation management: A review. Trauma. 2005;59(2):849-860.

-

Kim HK, Nelson LS. Reversal of opioid-induced ventilatory depression using naloxone. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28(4):377–382.

-

Marik PE. Pulmonary edema due to negative pressure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(1):64-68.